Opium

Excerpt Pages 178

Product. A poppy by any other name inebriates the same. Some call it “hop,” “midnight oil,” “tar,” “dope,” and “Big O.” At www.noslang.com you can find hundreds of street terms for opium and its derivatives (mainly morphine and heroin) from “antifreeze” to “zero.” The Greek ópion and the Latin opium both mean juice. The scientific name, Lachryma papaveris is Latin for poppy tears.

Excerpts Page 184 – 186

When I began the research to support this chapter my impression was that heroin was the big villain. It’s certainly powerfully bad stuff. It certainly is one of the foci of movies about drugs and DEA drug-bust publicity. For the last twenty years or so I have been gathering articles from the New York Times and other media about the various spices on my list. The stack regarding marijuana is by far the tallest. In the last year e-cigarettes has really taken off. Philip Seymour Hoffman’s heroin related demise in February 2014 gave a surprising boost to press attention to heroin. But heroin is by no means the most dangerous opioid. The worst are the prescription drugs already in your medicine cabinet.

Just a sampling of the pertinent statistics: Of the 2.5 million ER visits for drug overdoses in 2011, 1.4 million were related to pharmaceuticals. Of the 41,340 overdose deaths reported in that year, 22,810 (55 percent) were related to pharmaceuticals, and 16,917 (41 percent) involved opioid analgesics specifically. After marijuana at 36.4 percent, the past-year prevalence of abuse among American twelfth graders of opioids such as Vicodin (7.5 percent) and OxyContin (4.3 percent) exceed the use of the illicit drugs such as ecstasy (3.8 percent), inhalants (2.9 percent), cocaine in any form (2.7 percent), and heroin (less than 0.6 percent).1 And this part of the consumption story gets worse. Prescription opioid abuse appears to be an important first step in the direction of heroin use. Nearly half of the young people who inject heroin surveyed in three recent studies reported abusing prescription opioids before starting to use heroin. Some individuals reported taking up heroin because it was cheaper and easier to get than prescription opioids. Many also reported crushing opioid pillsto snort or inject the powder provided their initiation into these methods of consumption.

Excerpt Page 196

The main tool of promotion for opioids is personal selling, whether we are talking about heroin or the vast array of Schedule II opioids. It might be the teenager on a West Oakland street corner passing a packet through a car window to a Piedmont customer while talking up the next shipment. Or, maybe it’s a coat-and-tied “detail man” calling at a doctor’s office and leaving copious samples. The sales pitches in form are often the same. “I know you’ve used xxx in the past, but the new and improved version is even better.”

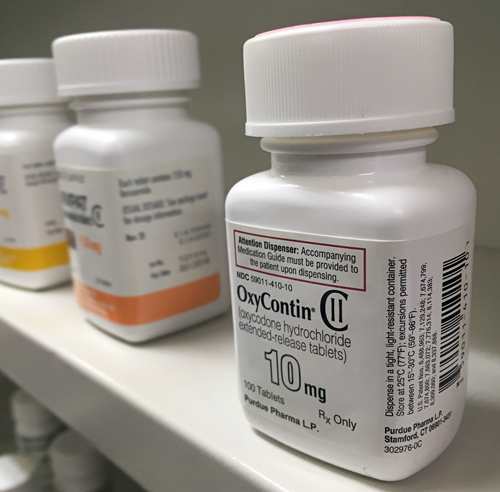

The classic case in the latter field is presented in the Journal of Public Health by Dr. Art Van Zee.1 For its rich and instructive detail we mightily admire his description of Purdue Pharma’s $200-million-per-year promotional

campaign and we excerpt his article heavily here:

Purdue “aggressively” promoted the use of opioids for use in the “non-malignant pain market.” A much larger market than that for cancer related pain, the non–cancer-related pain market constituted 86 percent of the total opioid market in 1999. Purdue’s promotion of OxyContin for the treatment of non–cancer-related pain contributed to a nearly tenfold increase in OxyContin prescriptions for this type of pain, from about 670,000 in 1997 to about 6.2 million in 2002, whereas prescriptions for cancer-related pain increased about fourfold during that same period…

A consistent feature in the promotion and marketing of OxyContin was a systematic effort to minimize the risk of addiction in the use of opioids for the treatment of chronic non–cancer-related pain. One of the most critical issues regarding the use of opioids in the treatment of chronic non–cancer-related pain is the potential of iatrogenic addiction. The lifetime prevalence of addictive disorders has been estimated at 3 percent to 16 percent of the general population…

In much of its promotional campaign—in literature and audiotapes for physicians, brochures and videotapes for patients, and its “Partners against Pain” Web site—Purdue claimed that the risk of addiction from OxyContin was extremely small.