Sugar

Excerpt Pages 47-48

Two-thirds of Americans are overweight, and one-third is obese. Between 30 and 50 percent of Americans are dissatisfied with their weight.1 Today some 100 million dieters are spending $20 billion a year trying to lose weight. Why is losing weight so difficult?

Sugar is not addictive. You get habituated to sugar, which is not being addicted.

STEFAN CATSICAS, CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER, NESTLÉ

Bloomberg BusinessWeek tells us Dr. Catsicas is a a quadrilingual Swiss neuroscientist. But he apparently doesn’t understand English very well. Or perhaps he’s a bit biased by his nice Nestlé salary? Sugar is an addictive compound. Some criticize this label as it equates eating disorders with harddrug addictions. Certainly the sugar industry hates the idea of being lumped together with drug dealers. But that is precisely the conclusions drawn by a National Institute of Health sponsored study by three psychologists at Princeton:

From an evolutionary perspective, it is in the best interest of humans to have an inherent desire for food for survival. However, this desire may go awry, and certain people, including some obese and bulimic patients in particular, may develop an unhealthy dependence on palatable food that interferes with well-being. The concept of “food addiction” materialized in the diet industry on the basis of subjective reports, clinical accounts and case studies described in self-help books. The rise in obesity, coupled with the emergence of scientific findings of parallels between drugs of abuse and palatable foods has given credibility to this idea. The reviewed evidence supports the theory that, in some circumstances, intermittent access to sugar can lead to behavior and neurochemical changes that resemble the effects of a substance of abuse. According to the evidence in rats, intermittent access to sugar and chow is capable of producing a “dependency”. This was operationally defined by tests for binging, withdrawal, craving and crosssensitization to amphetamine and alcohol. The correspondence to some people with binge eating disorder or bulimia is striking, butwhether or not it is a good idea to call this a “food addiction” in people is both a scientific and societal question that has yet to be answered. What this review demonstrates is that rats with intermittent access to food and a sugar solution can show both a constellation of behaviors and parallel brain changes that are characteristic of rats that voluntarily self-administer addictive drugs. In the aggregate, this is evidence that sugar can be addictive.

And, that is precisely my fundamental argument in this book – hedonic molecules such as sugar and cocaine should be thought of in similar ways. Craving, binging, and withdrawal are all terms I associate with my own rat-like relationship with sugar. So I use the term “sugar addiction” herein without hesitation.

Excerpt Pages 57-59

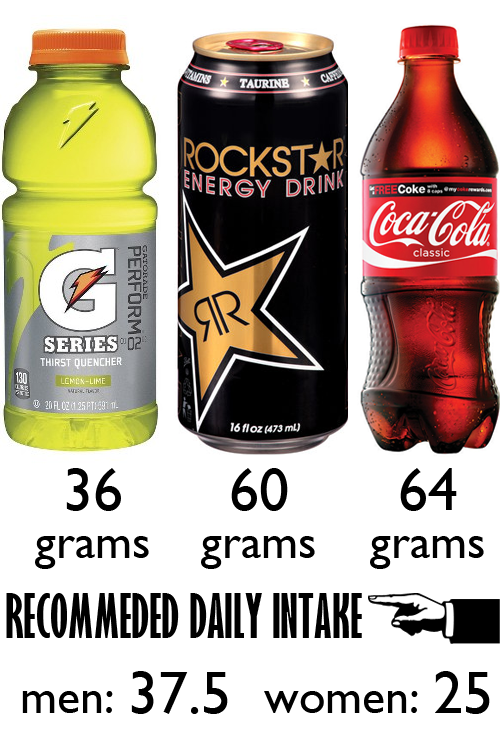

Promotion. Since most (80 percent+) sugar is reaching American stomachs as a processed food ingredient, most of the promotional efforts involve the big food processors, beverage companies, and restaurant chains. And, most of the promotional dollars spent by those firms are in the form of mass-media advertising. Personal selling by both sugar and beverage firms to commercial customers such as McDonald’s is also a very important aspect of competitive marketing practices, but those efforts are more difficult to track and analyze. So we will focus on mass-media advertising here. We do note, however, that the sugar producers’ budgets for public relations and legal services have ballooned during the recent civil war between sucrose and HFCS producers.

Advertising. You will see in Exhibit 3.6 that six of the top twenty global advertisers are delivering sugar to their customers. That’s almost $22 billion dollars globally and almost $5 billion domestically being spent on ads by only six companies to convince you to buy their sugared products. The six largest automobile manufactures spent less, only $15.5 billion in the same time period.

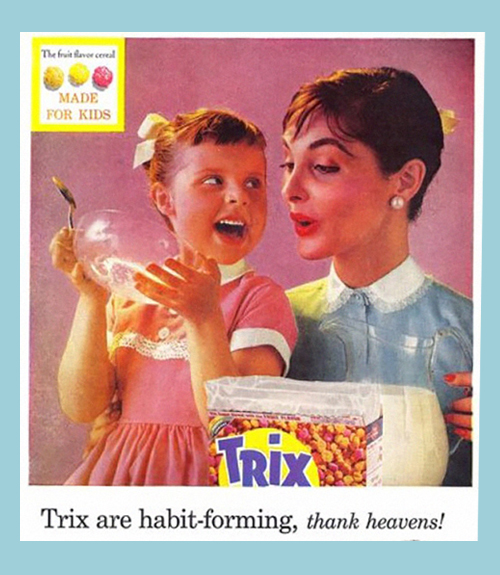

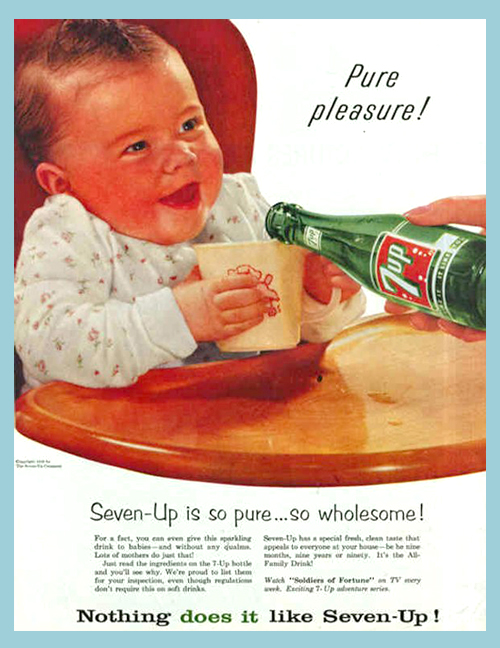

Public Relations. These massive efforts to influence behavior and public opinion thoroughly dominate the debate on the public health. As we said in the last chapter, when the US corporations weigh shareholder interests against those of the public health, the choices almost always favor shareholders. Indeed, recently the large beverage companies spent $4.1 million fighting beverage tax initiatives in two small cities in California. Or consider the consequences of the US Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) attempts to regulate the advertising of sugared cereals to American children in the late 1970s. The maelstrom of public relations and lobbying by the industrial giants almost destroyed the FTC itself. Regulators have remained gun shy since.